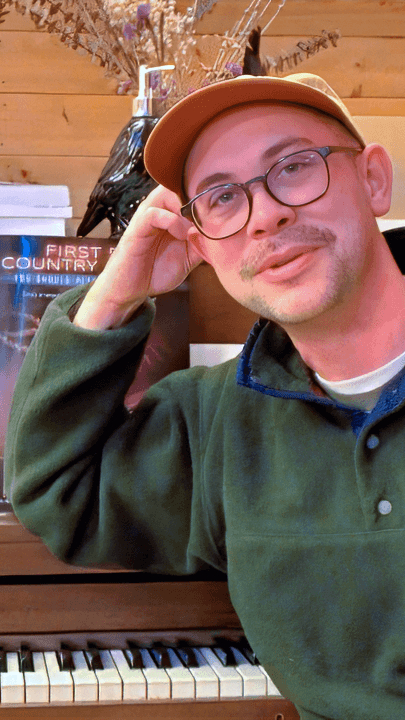

Dr. Jeremy Smith, a composer from the Shoals, Alabama, crafted a full orchestral work inspired by American folk music during his residency at Azule. Commissioned by a Washington, DC-based ensemble through a grant supporting music rooted in folk traditions, Jeremy draws from classic river songs like “Down by the River,” “Shenandoah,” and “Shall We Gather at the River.” His piece, Creek Don’t Rise, honors both this musical heritage and those affected by Hurricane Helene, bringing attention to overlooked stories through sound.

Starting with just a few minutes sketched before arrival, Jeremy has expanded the composition to nearly eight minutes, working deliberately in the quiet Appalachian setting. This space allows him to slow down, reflect, and shape his music with clarity and purpose—values that echo his lifelong dedication to simplicity and structure.

From childhood memories of singing in church and a youthful fascination with Elvis, to formal training as a percussionist, Jeremy’s journey is marked by a commitment to disciplined artistry. His work reflects not only folk traditions but also his personal search for balance between emotion and order in music.

You can follow along with Jeremy’s journey on Instagram: @jeremy_smith_composer or visit their website at rwsmusic.com/composers/jeremy-smith.

Watch our Full Conversation

Transcript

I’m Dr. Jeremy Smith. I’m a composer from the Shoals, Alabama, and I’m here working on a piece for full orchestra. What I’ve been working on since I’ve been here — I thought I was gonna do 12 things, but I’m about to finish one. I was commissioned by a group in the larger DC area to write a piece, and they wrote a grant for music inspired by American folk music. So, it’s for a full orchestra, and it was supposed to take inspiration from American folk music.

I’ve been working through, over the last couple of months, just kinda doing research and listening and trying to figure out which songs I wanted to include. So when I came here, I had about three and a half minutes kind of sketched out, and since then I’ve written another four and a half. So I’m about eight minutes now. It’s really done — I have to do one last little section at the end.

I’ve been working on putting all that together. Being here, for me, is always really nice to come back. There’s just an energy here, and a quietness, and something that allows you to be intentional and take your time doing things — to just get away from the rat race, you know. Plus, I think there’s a history of folk music here. I mean, this is Appalachian music — why not come to the most Appalachian place you can to do that, right?

There was always an interest in music for me. When I was around four or five, I got a VHS — Elvis, actually. I just became enamored with Elvis — probably a hyperfixation on Elvis. I would go to the bathroom when I was in preschool and put soap in my hair, slick it back, and be like Elvis. Ever since I can remember, I’ve been interested in music.

I grew up in the church, singing in Church of Christ — we did acappella singing. That’s kind of where my background and a lot of my by-rote training came from. Then I joined band when I was 12 and started studying music more formally as a percussionist. That led to me going to college and continuing to pursue music. I started writing in college, and that’s where it really took off.

The unifying artistic inspiration I have — it’s more about values. I’m really big on simplicity, clarity, structure — those sorts of really disciplined values. That’s what’s so beautiful to me about music and about art in general — we get to make that. Those are things I wish were in my life more. I wish I was like that more: more clear, more simple, more disciplined, etc.

Music gives me an outlet to do that, but also to try again and over and over. You finish a piece and look back and say, “I could’ve done x, y, and z,” but you let it be done and you move on to the next one. The artistic life is built around trying to embody these values that I have, and obviously it manifests in different ways with different projects. But yeah — that’s the overarching goal and inspiration.

The piece is called Creek Don’t Rise, which is like — obviously — the Southern “Good Lord willin’ and the creek don’t rise.” The idea started with wanting to use a Southern idiom like that. The pieces I liked and pulled from — Down by the River (an old fiddle tune), Down to the River to Pray, Shall We Gather at the River, Shenandoah (the state song of Virginia, where I was commissioned) — they were all about rivers.

Then I realized — when I was coming here — I wanted to dedicate it to those affected by Hurricane Helene. I want to talk about that and the kind of damage. Being in Washington, DC — this storm didn’t get talked about because the election was going on, and there was so much other stuff happening, people just forgot about the damage in this area.

So in whatever way I can bring awareness to it — maybe a couple months too late, but maybe not.

There’s a background on it for you — but I’ll play it for you now.

This part, I gotta finish at the end.

Great. So I love how dynamic it is — the homage you paid to so many different styles. That’s great.

Yeah, I tried to do, like, a waltz, a two-step. I did research — I knew some of it before, but you can’t do that stuff without really looking into it. Otherwise, it’s just a cheap ripoff.

And there’s some stuff I didn’t change all that much — it just works so well kind of as it is. So yeah, I’m almost done.

I gotta finish, like, that much. You see where it just gets ready to finish? I gotta finish that much, and then I’ll be done. I might put a little tail end on it that fades out, but yeah — I’m really close to being finished with it.